- Heritage Issue

- Heritage Walk

- Muziris Heritage Project

- Kerala Monuments

- Syrian Christians

- Prevalence of Jainism

Preserving Thrissur’s heritage

PHOTO: K.K. NAJEEB

LIVING WITH CHANGE: Thrissur is witnessing fastpaced change.

High-rise buildings at Pazhayanadakkavu in the city.

Thrissur, rebuilt by Sakthan Thamburan, used to be an elegant, well-planned town. It was developed around a hillock with Sree Vadakkunnathan Temple on top and is surrounded by the Thekkinkadu Maidan.

The lush green maidan, which became the core of the town, is a rare luxury as very few towns have such a breathing space. Swaraj Round, the large ring road around the core and lanes originating from it, proved to be the perfect road system.

Heritage buildings and structures stood with pride around Swaraj Round. The huge ‘tharavads’ (traditional Kerala houses) along the lanes such as Kuruppam Road and Marar Lane were monuments to Kerala’s architectural traditions. Brahmin madoms at Pazhaya Nadakkavu, established by Sankaracharya’s disciples, were unique structures.

The vast wetlands around the town acted as a reservoir of water and absorbed the rainwater. Water-logging was never a problem.Thrissur’s reputation as a heritage town, however, started fading with the intense urbanisation in the past quarter century. The spurt in population has hurt the architectural heritage and the orderly urban ambience of Thrissur. The “tharavads” gave way to multi-storeyed modern commercial buildings. The huge apartment complexes that mushroomed in the city during the past decade stood out mostly as eyesores. The old infrastructure proved insufficient when the town got transformed into a busy urban centre. The roads became crowded and congested.

A recent seminar organised in the city by the Indian National Trust for Art and Cultural Heritage (INTACH) highlighted the urgent need to preserve the remaining heritage structures, which were on the verge of extinction.

“Haphazard development with short-term goals defaced the city,” the former Chief Town Planner Kasthuri Rangan said. He called for an integrated planning package for the city as well as its outskirts to decongest the city. Though development was inevitable for any growing city, it should be in such a manner that the traditional landscape and culture is preserved, says M.M. Vinod Kumar, an architect interested in heritage preservation.

“We need to study the fabric of the city, its architectural language and conservational possibilities before changing the original character of the city with new structures,” he told The Hindu.

The huge cost of maintenance and shortage of skilled labourers were the main challenges to the conservation of heritage buildings. Many of the ‘tharavads’ were rich in wooden carvings. Only two or three old persons stayed in most of these huge buildings, which were once home to dozens of family members and servants. If unused, termites would finish the elegant woodwork of these houses in no time.

“Reusing these tharavads as heritage home-stays without changing their external structures and elevation is one of the viable options to preserve them,” Mr. Vinod Kumar said.

Experts suggest that areas with many traditional structures should be declared heritage zones as in Fort Kochi. Thrissur has a huge potential for heritage tourism, they feel. “We should get the pilgrims to Guruvayur to stay here for some time,” Mr. Rangan said.

MINI MURINGATHERI

Muziris Heritage Project to open on February 18

K.P.M. Basheer

PHOTO: Thulasi Kakkat

Archaeological excavations being undertaken at Pattanam, a village near Kochi.

Pattanam has been identified as Muziris, the ancient port described in Roman and Tamil Sangam texts..

KOCHI: The Muziris Heritage Project, a unique tourism and heritage conservation project linking monuments in the area surrounding the bygone 2,000-year-old Muziris port, will be opened to the public next month.

Finance Minister T.M. Thomas Isaac, the prime mover of the project, told The Hindu that the site would be opened on February 18 by Union Tourism Minister Selja. Most of the work being undertaken as part of the project would be ready by then, he said.

Sources, however, said the inauguration, initially set for late March or thereafter, was being hurried in view of the Assembly election expected in April. Once the election is notified, it would not be possible to hold the opening ceremony until after the elections are over and a new government takes office. The Left Democratic Front government is keen to get the project off the ground before its term ends.

Dr. Isaac said the project, which would include parts of North Paravur and Kodungalloor municipalities and seven grama panchayats, would be a unique tourism project in the country. “You will be walking through history in the Muziris Heritage Tourism Circuit — through the layers of Dutch, Portuguese, Roman and Arabian histories.”

Four museums

By March, four museums, Paliam Nalukettu, Paliam Kovilakam (Dutch Palace), the Paravur synagogue and the Chendamangalam synagogue, are expected to let in visitors.

Two boat services, which will link the monuments, will be started.

These services, one from the Paravur market and the other from the Kottappuram market, will take tourists down memory lane. Some of the monuments on the way would be: Pallipuram Fort, Vyppikota Seminary, Holy Cross Church, the newly discovered Jewish cemetery, and Kottayil Kovilakam. The excavations at Kottappuram Fort will also be opened to the public.

The Union Tourism Ministry has allocated Rs.40 crore for the Muziris Heritage Tourism Circuit. However, the Kerala government sees the project mainly as a heritage conservation project with tourism add-ons. It has been declared as the first green project of the Kerala government. Some 19 government agencies and departments are involved in the project, apart from local government bodies in the area.

Major attractions

One of the major attractions of the project is the archaeological excavations at Pattanam, believed to be the ancient town that acted as a backup to the Muziris port, which was located close to Kodungalloor.

Merchants at Pattanam had brisk trade with the ancient world, Rome, Arabia, Egypt and Greece. Muziris, then located at the mouth of the Periyar river-Arabian Sea, is believed to have been washed under the sea during the AD 1341 flood in the river.

The Muziris Tourism Circuit includes not only the remnants of Muziris and Pattanam, but also monuments from the Dutch, Portuguese and English colonial periods. The project is also envisaged as a non-formal academic site for the study of Kerala history, archaeology, folklore etc.

World heritage status sought for Kerala monuments

Thrissur: Efforts are on to get iron-age burial grounds and monumental temples of Kerala included in the World Heritage List, M. Nambirajan, Superintending Archaeologist, Archaeological Survey of India, Thrissur circle, has said.

He was addressing a national seminar on ‘Linking archaeology and history: the Kerala contest' at the Kerala Sahitya Akademi hall here on Saturday.

The UNESCO World Heritage List comprises heritage and cultural properties, which the World Heritage Committee considers as having outstanding universal value. The Heritage List includes 704 cultural, 180 natural and 27 mixed properties.

“The Archaeological Survey of India and State Archaeological Department have prepared separate lists of monuments to get conferred with the world heritage status. The ASI list includes a group of monumental temples, burial grounds and forts. Edakkal caves and Sri Padmanabha Swami Temple are there in the list of the Archaeological Department,” Mr. Nambirajan said.

As of now, the State does not have any monument with World heritage status. Under the jurisdiction of the Kerala unit of the ASI based in Thrissur, there are 27 protected monuments of Kerala and 10 of Tamil Nadu. Mr. Nambirajan said the objective of the seminar was to create awareness and interest among youngsters about historical monuments and heritage structures in the country.

Speaker K. Radhakriahnan inaugurated the seminar.

Delivering the key-note address on ‘Epigraphical researches in Kerala – problems and prospects', historian and epigraphist M. R. Raghava Warrier said that the popular method of paraphrasing the epigraphs was unscientific.

The Archaeological Survey of India, Thrissur circle, in association with the Kerala Historical Research Society organised the seminar in connection with the World Heritage Week.

A photo exhibition of world monuments was organised at the venue.

Tracing the heritage of Syrian Christians

The Nomocanon of Abdisho of Nisibis

Thrissur: A project to trace, catalogue and digitise lost documents relating to the religious practices, culture and heritage of the Syrian Christians of Kerala has been launched with the support of some European universities and local historical research bodies.

The project's main objective is to unearth valuable 16th and 17th century documents in Syriac, vandalised or stashed away by Portuguese missionaries in their quest for bringing the ancient Christian community of India under Papal dominance, Metropolitan Mar Aprem, Metropolitan of the Church of the East, said.

As the initial result of the programme, a facsimile edition of a manuscript has been brought here after its original text disappeared seven centuries ago.

Local church historians and secular scholars maintain that a large volume of literature on the Syrian Christian culture and heritage was burnt by the Portuguese missionaries after the historic Synod of Diamper, held at Udayamperoor, near Kochi, in 1599, that offered a last chance to non-Catholic denominations to fall in line. The text, known as Nomocanon of Abdisho of Nisibis (Canon Law), was compiled by the Metropolitan of Nisbis and Armenia in 1291 AD in his own hand.

The prelate died in 1318 AD, he said. The revived text was edited by Istva Prczel of Central European University, Budapest, formerly researcher at the Oriental Institute, Tubingen University, Germany.

The manuscript was submitted before the Thrissur district court and legally approved as the authentic law of St. Thomas Christians of Kerala, Mar Aprem said.

The oldest and most important manuscript ‘Kashkol' (breviary-prayer book) also miraculously survived destruction by the Portuguese inquisitors, he said.

The St. Thomas Christians of Kerala, now divided into various denominations, including the Catholic fold, trace their origin to the arrival of St. Thomas the Apostle at Kodungalloor in AD 52 to preach the Gospel.

Over the centuries, the community followed eastern rites and liturgy. This brought them in conflict with the Portuguese missionaries who arrived in Kerala in the 15th and 16th centuries and wanted the entire community to be brought under Catholic control.

The Synod of Diamper called by them attacked the customs of the St. Thomas Christians and even their version of the Bible, liturgy and theology and burnt many of their texts.

This event, rather than weaken, strengthened the St. Thomas sect's spirit to defend their culture and heritage and they fought against the ‘Latinisation' process unleashed by the Portuguese missionaries, Mar Aprem said.

As part of the resistance to the ‘Latinisation' campaign, community leaders congregated at Mattanchery, near Kochi, in January 1653 and took a vow not to fall in line. This event was known as the ‘Bent Cross Oath' or ‘Coonan Kurishu Sathyam' in Kerala history.

The facsimile edition of the canon law was published by the Georgias Press LLC, U.S., as part of an extensive project to survey, catalogue and digitise manuscripts in Syriac, Mar Aprem said.

The project also seeks to unearth and preserve other material relating to over 2,000 years of Christianity in the State. — PTI

Tamil-Brahmi script found at Pattanam in Kerala

T.S. Subramanian

Photo: P.J. Cherian

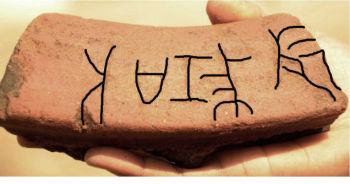

The Tamil-Brahmi script with the letters "a ma na," meaning Jaina,

found at Pattanam in Kerala. The letters are followed by two

megalithic graffiti symbols which could not be identified.

CHENNAI: A Tamil-Brahmi script on a pot rim, reading “a ma na”, meaning a Jaina, has been found at Pattanam in Ernakulam district, Kerala, establishing that Jainism was prevalent on the west coast at least from second century CE (Common Era). The script can be dated to circa second century CE. The three Tamil-Brahmi letters are followed by two symbols generally called Megalithic graffiti and these two symbols could not be identified. This is the third Tamil-Brahmi script to be found in the Pattanam excavations.

The Kerala Council for Historical Research (KCHR) has been conducting excavations at Pattanam since 2007, with the approval of the Archaeological Survey of India. The pot-rim was found during the sixth season of the excavation currently under way. Pattanam is now identified as the thriving port called Muziris by the Romans. Tamil Sangam literature celebrates it as Muciri.

P.J. Cherian, Director of the Pattanam excavations, said: “The discovery, in the Kerala context, has a great significance because of the dearth of evidence so far of the pre-Brahminical past of Kerala, especially in relation to the socio-cultural and religious life of the people. We have direct evidence from Pattanam now with the Brahmi script which mentions “a ma na” [Jaina] and so we have evidence that Jainism and Buddhism were extensively practised in Kerala.”

Iravatham Mahadevan, a scholar in Indus and Tamil-Brahmi scripts, said the discovery showed that “there was Jainism on the west coast at least from second century CE. The importance of the finding is that it stratigraphically corroborates the earlier datings given to the Tamil-Brahmi cave inscriptions in Tamil Nadu on palaeographic evidence. I will date this sherd, on palaeographic evidence, to circa second century CE.”

The Tamil word “a ma na” meaning a Jaina was derived from Sanskrit Sramana via Prakrit Samana and Tamil Camana, said Mr. Mahadevan. The two megalithic graffiti, following the three Tamil-Brahmi letters, could not be identified. “But we know from similar finds in Tamil Nadu, especially at Kodumanal, that Tamil-Brahmi letters and megalithic graffiti symbols occur side by side,” he said. Mr. Mahadevan was sure that “many more exciting finds will be made at Muciri [Pattanam] which was a flourishing port on the west coast during the Sangam age in Tamil Nadu, which coincided with the classical period in the West.”

Mr. Cherian, who is also Director of KCHR, said the discovery “excites me as an excavator because it was for the first time we are getting direct evidence relating to a religious system or faith in Kerala.” The pot might have belonged to a Jaina monk. The broken rim with the script was found at a depth of two metres in trench 29 in the early historical layer which “by our stratigraphic understanding could belong to third-second CE period,” he said. The associated finds included amphora sherds, iron nails, and beads among others.

In a trial trench laid earlier at Pattanam by Professor V. Selvakumar, Assistant Professor, Department of Archaeology and Epigraphy, Tamil University, Thanjavur and K.P. Shajan of KCHR, a pot-sherd with the Tamil-Brahmi letters reading “ur pa ve o” was found. Later, another Tamil-Brahmi script with the letters “ca ta [n]” was found.

Mr. Mahadevan praised the Pattanam excavations as “the best conducted excavations in south India.” He said it was “a potentially important site and excavations are being done in a competent way by Mr. Cherian and his team from the KCHR and they have involved experts from around the world.”